Carr & Day & Martin Ltd

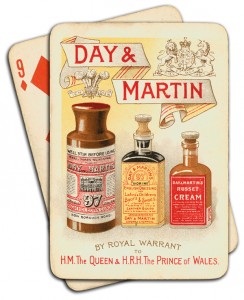

The exact starting date of Charles Day’s blacking business and it’s origins are unclear (although all the products proclaim “established 1770”). The story, endorsed in the present company’s publicity, goes that the young Mr Day, then a Doncaster hairdresser by trade, gave shelter for the night to a wandering soldier. The soldier was not able to pay Day for his hospitality, and instead provided him with the recipe for boot blacking which he had concocted to polish the boots of his superior officers and that together they opened a little shop at 97, High Holborn, London in 1770. However, the story was denied by Day in 1835 and there is a counter-story in which the recipe for blacking preparation was communicated to Mr. Richard Martin whilst Day was travelling on the continent. Martin afterwards became associated with Mr. Charles Day, and in 1801 they commenced the manufacture of blacking at 97 High Holborn.

The exact starting date of Charles Day’s blacking business and it’s origins are unclear (although all the products proclaim “established 1770”). The story, endorsed in the present company’s publicity, goes that the young Mr Day, then a Doncaster hairdresser by trade, gave shelter for the night to a wandering soldier. The soldier was not able to pay Day for his hospitality, and instead provided him with the recipe for boot blacking which he had concocted to polish the boots of his superior officers and that together they opened a little shop at 97, High Holborn, London in 1770. However, the story was denied by Day in 1835 and there is a counter-story in which the recipe for blacking preparation was communicated to Mr. Richard Martin whilst Day was travelling on the continent. Martin afterwards became associated with Mr. Charles Day, and in 1801 they commenced the manufacture of blacking at 97 High Holborn.

Whatever the exact origins the business was a success and the small premises soon gave way to a purpose built palatial factory with a grand exterior facing High Holborn and premises extending a considerable distance back. The photo (right) shows the site today, the original building gone with a hotel now in its place. The parcel of land it occupies is much the same as the original factory though, extending back to Eagle Street.

Whatever the exact origins the business was a success and the small premises soon gave way to a purpose built palatial factory with a grand exterior facing High Holborn and premises extending a considerable distance back. The photo (right) shows the site today, the original building gone with a hotel now in its place. The parcel of land it occupies is much the same as the original factory though, extending back to Eagle Street.

Mr Day had a flair for publicity (as did his main blacking competitors) and magnificent black horses were used to draw the Day & Martin carriages as they delivered their products throughout London. It is said that these same horses were borrowed for the state funeral of the Duke of Wellington. Apart from the horses themselves, the firm had wonderful stables and equipment and used to take all the prizes at local shows and events. An interest in equestrian products so developed, the first equestrian product made being Belvoir Bar Soap which is still made today to the original glycerine formula.

Charles Day married Rebecca Peake at Stafford St. Mary’s on 6th September, 1806. They had one daughter, Letitia Caroline, (c1808-1877), who when young was a sought after heiress until she eloped with Horatio Clagett (or Claggett), a well-known “playboy” and serial bankrupt, in 1832. In 1823 a John Weston is mentioned in insurance records, possibly he was the factory manager.

Charles Day died on the 25th October 1836 leaving some £450,000 and was buried at St Margaret’s, Edgware. The will mentions his main residence as Harley House, Regents Park. He also owned a second house, Edgware Place, which stood in the village of Edgware at the junction of Watling Street and the road now called Manor Park Crescent. This was built c. 1803 by the Hon. John Lindsay, afterwards becoming the residence of Charles Day, who built for it a lodge known as Blacking-Bottle Lodge, because its shape represented one of the bottles in which Day and Martin packed their liquid boot-blacking. The house had been demolished by 1845 but the lodge remained for long after that date. He also left £100,000 to found an institute for the blind, Blind Man’s Friend (known as Day’s Charity) for the benefit of persons suffering under the same affliction as himself of many years – ‘deprivation of light’. In 1860 240 blind persons received £3,528, in sums varying from £12 to £20 each. This Charity was later administered by the Clothworkers’ Company. Also the almshouses were conveyed to trustees. Day’s will contained five codicils made in the weeks before his death and was heavily contested for several years. His widow Rebecca lived on at Edgware with her daughter and son-in-law until her death in 1843.

Charles Day died on the 25th October 1836 leaving some £450,000 and was buried at St Margaret’s, Edgware. The will mentions his main residence as Harley House, Regents Park. He also owned a second house, Edgware Place, which stood in the village of Edgware at the junction of Watling Street and the road now called Manor Park Crescent. This was built c. 1803 by the Hon. John Lindsay, afterwards becoming the residence of Charles Day, who built for it a lodge known as Blacking-Bottle Lodge, because its shape represented one of the bottles in which Day and Martin packed their liquid boot-blacking. The house had been demolished by 1845 but the lodge remained for long after that date. He also left £100,000 to found an institute for the blind, Blind Man’s Friend (known as Day’s Charity) for the benefit of persons suffering under the same affliction as himself of many years – ‘deprivation of light’. In 1860 240 blind persons received £3,528, in sums varying from £12 to £20 each. This Charity was later administered by the Clothworkers’ Company. Also the almshouses were conveyed to trustees. Day’s will contained five codicils made in the weeks before his death and was heavily contested for several years. His widow Rebecca lived on at Edgware with her daughter and son-in-law until her death in 1843.

These almshouses were built by Charles Day in 1828. There are eight of them on a 1 acre plot fronting onto Watling Street at Stone Grove which he bought from All Souls College. During his lifetime Day selected the almspeople. By his will, he conveyed the almshouses and land to trustees, leaving sufficient money to provide an endowment of £100 a year for the upkeep of the property and weekly payments to the almspeople. In selecting almspeople the trustees were to give preference to parishioners of Edgware and Little Stanmore, providing that they did not sell or drink intoxicants, swear, or break the Sabbath. The almshouses consist of a long single-storied range in an early-19th-century Gothic style with steep gables, pinnacled buttresses and a slate roof. The front is faced with stone ashlar and has Gothic arcading below the eaves and verges. In the central gable, which is flanked by two smaller ones, is a clock and the date 1828. In 1886 one of almshouses were damaged by a fire but the development was sympathetically restored in 1959 to its former glory. In 1964 the income of the endowment was just £278 and, proving insufficient to make payments to the occupants, expenditure was limited to the upkeep of the buildings only.

These almshouses were built by Charles Day in 1828. There are eight of them on a 1 acre plot fronting onto Watling Street at Stone Grove which he bought from All Souls College. During his lifetime Day selected the almspeople. By his will, he conveyed the almshouses and land to trustees, leaving sufficient money to provide an endowment of £100 a year for the upkeep of the property and weekly payments to the almspeople. In selecting almspeople the trustees were to give preference to parishioners of Edgware and Little Stanmore, providing that they did not sell or drink intoxicants, swear, or break the Sabbath. The almshouses consist of a long single-storied range in an early-19th-century Gothic style with steep gables, pinnacled buttresses and a slate roof. The front is faced with stone ashlar and has Gothic arcading below the eaves and verges. In the central gable, which is flanked by two smaller ones, is a clock and the date 1828. In 1886 one of almshouses were damaged by a fire but the development was sympathetically restored in 1959 to its former glory. In 1964 the income of the endowment was just £278 and, proving insufficient to make payments to the occupants, expenditure was limited to the upkeep of the buildings only.

The competition – 1811

To COUNTRY SHOPKEEPERS and OTHERS.

WHEREAS, a Set of SWINDLERS are now travelling the country to solicit orders in the names of DAY and MARTIN, Blacking Makers, 97, High Holborn, London. Shopkeepers and others are, therefore cautioned from the fraud that is attempted to be practised on them, as by paying attention to the No.97, it will easily detect the counterfeit, many of them having no number at all; and prosecutions, after this notice, will be commenced against any person offering the counterfeit for sale. N.B. No Half Pints made. London, March 30, 1811.

The competition – 1821

COURT 0F KING’S BENCH, GUILDHALL. – Day and Another v. Brown

This was an action by Messrs. Day and Martin, blacking-makers, against the defendant, Henry Brown, for an imitation of their label. The trick was discovered by a typographical error in the counterfeit: the damages were laid at £1,000.

Mr. Scarlett felt no hesitation in opening the case, as one of the darkest which had ever been presented to a jury. To introduce the present plaintiffs formally to the jury, would scarcely be requisite; for who, with the slightest pretension to polish, could be unacquainted with the names of Day and Martin? Could it be necessary to say, that those gentlemen by stooping to the feet, had raised themselves to the head of society? Needed it to be observed in the year 1821, that their fame had spread through every clime, where shoes were made of leather? Did not their puffs and poems (surpassing even those of Packwood) enrich every newspaper of the day? and would not they themselves go down to posterity the blackest, yet the brightest, characters of the age? The jury were men; and they would know mankind. The jury wore boots; and they would know the merits of Martin’s blacking; of that inestimable fluid, -dark as the jetty plumage of that bird, whose name the maker bore. But fame raised enemies; success raised rivals; and, even as with others, so had

it fared with the present plaintiffs. Pretenders had put up for public favour; but frail as their own bottles had been their standing in the trade; like those bottles, they had broken; and the long hands of sweeping assignees. bad left not a hamper behind. Yet there was one – and now the learned counsel came to the gravamen of his case – there was one man who played a deeper game. An envious oil-man dwelt near Golden-square, who saw and grudged the plaintiffs rising fortunes. The caitiff’s name was Brown; and he could make a liquid which he called black, but which, like him, was brown. Each flask, like Pandora’s box, contained thousand ills: it burned up good men’s shoes, did harm to harness, and, lustreless, defied the sweating valet’s toll. To sell this, villainous composition, however, was Brown’s chiefest care; and how did the jury think the wicked end had been attained? Knowing that his own name would bring no buyers, the man of guile resolved to take another’s: he printed a quantity of labels in imitation of the labels of the plaintiffs; pasted them at leisure upon his spurious bottles; and uttered his own base compound to the world, as the genuine blacking of the illustrious Day and Martin. The plaintiffs did not ask vindictive damages, but the defendant, they submitted, was a double trespasser; at once, a depreciator of their inestimable ware, and a destroyer of the shoes and boots of the community. The plaintiffs were not the only persons who within the last few years had suffered by such mean and piratical practices. There was a Mrs. Lazenby who had discovered a pickle so piquant as to tickle the palates of all the aldermen in London – she had been unable to’ keep possession of her own name. A Mr. Cox, too, the inventor of a most delicious sauce, had been obliged to protect himself by law: and the learned counsel really apprehended, unless the jury made an example of the present defendant, that some rogue would go down into the country, redden his face, put on a powdered wig, and call himself Mr. Scarlett; or, playing the same trick upon the learned solicitor-general, receive all those fees and emoluments of office, to which that learned gentleman stood entitled.

Mr. E. Custance had been many years in the habit of using Day and Martin’s blacking. He bought a bottle of blacking (purporting to be of Day and Martin’s manufacture) from the defendant Brown. Finding it vile stuff, he carried it to the house of the plaintiffs in High Holbom, who abjured it.

James Barton proved the purchase of a similar bottle. The counterfeits were then put in.

Thomas Richardson was printer to the Plaintiffs. Their labels were printed from a stereotype plate. He could swear, that the labels of the spurious bottles were not printed from the plate of the plaintiffs. There were several typographical errors: among others, the word “inestimable” in the true bill. stood” inestmiable” in the counterfeit.

Richard Brown, first cousin to the defendant, admitted, that he had got about 2,400 labels struck off from a plate, which was supplied to him by the defendant.

Mr. Denman addressed the jury in mitigation, but called no witnesses.

The lord chief justice thought it a case not for vindictive, but certainly for reasonable damages.

The jury found a verdict for the plaintiffs. – Damages £15.

Day and Martin blacking factory, 97 Holborn, London. 1842

Packing-Warehouse - Day and Martin's blacking factory

All the world has heard of “Day and Martin” The two names are so associated that we can hardly conceive a Day without a Martin, or a Martin without a Day; and that either Day or Martin should ever die, or be succeeded by others, seems a kind of commercial impossibility – a thing not to be thought of.

All the world has heard of “Day and Martin” The two names are so associated that we can hardly conceive a Day without a Martin, or a Martin without a Day; and that either Day or Martin should ever die, or be succeeded by others, seems a kind of commercial impossibility – a thing not to be thought of.

“Day and Martin” it has been for forty years, and “Day and Martin” it will probably be for forty years to come, or perhaps till blacking itself shall be no more.

To “Day and Martin’s,” then, the reader’s attention is directed.

The full 1842 Penny magazine article complete with engravings entitled “A day at Day & Martin’s” published by “The Office of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge” can be read here.

Fire at Day and Martin’s, New Zealand Wellington Independent, 13 November 1869

Shortly after 11 o’clock on Friday night, September 3, a fire was discovered in the blacking establishment of Messrs Day and Martin, Holborn. The premises consisted of offices fronting the street, and a manufactory, separated from the fore part by an open courtyard. It was in the manufactory that the fire broke out, and the inflammable character of the materials with which the place was stored soon created an extraordinary body of flame. The building extended from Holborn to Eagle street, several hundred feet in depth, and when the firemen arrived the whole interior, from end to end, was one mass of flame. A very large force of engines was summoned to the spot, and an immense volume of water poured into the building from several points; but all the efforts of the firemen failed to reduce the flame until it had almost exhausted itself; and then the outer walls and iron girders of floor and roof were all that remained. About 1 o’clock the fire was extinguished, the premises being a total wreck. The loss to the firm is covered by insurance. The fire was attended by a fatal result. A man named Evans, who had been courageously assisting to arrest the progress of the fire, was precipitated, some time after the flames had been got under, into a tank of vitriol, and died in a few hours.

Fire at Nine-Elms, Illustrated London News, March 12 1870

The fire which broke out, at ten o’clock in the evening of Wednesday week, in the newly-built factory of Messrs. Day and Martin, blacking manufacturers, in Vauxhall-road, Nine-elms, destroyed a large amount of property. The building, about 250ft in length, contained a quantity of oils, vitriol, and other inflammable substances, which caused the fire to spread very quickly; and, as the flames rose high into the air, the sight from the opposite side of the Thames was both terrible and grand. The steam fire-engines arrived early and got an abundant supply of water, but it was an hour before they could subdue the conflagration. The official report of the damage was as follows:- “Messrs. Day and Martin, blacking makers. A building of two floors, used as paper, oil-saturating, and drying rooms, 200ft long and 27ft broad, nearly burnt out, and most part of roof off. Messrs. Rolfe and Gardiner, lath-renders. A building of one floor, 200ft long and 27ft wide, all adjoining and communicating, damaged by breakage and water. Lambeth Supplementary Workhouse. The ground floor severely damaged by water, &c. Messrs. Day and Martin were not insured. The origin of the fire is unknown.”

A new start – 1889

With the High Holborn factory destroyed by fire in 1869, the building of a new factory next to the Thames, and that new premises meeting the same fate barely six months later in 1870, times must have been very turbulent for the company. Sun Fire Office records show the High Holborn works had fire insurance in 1823, 1824 and 1825 – insurance was in place in 1869 to cover the High Holborn fire but the fire at the new factory at Nine Elms wasn’t insured for some strange reason.

With the High Holborn factory destroyed by fire in 1869, the building of a new factory next to the Thames, and that new premises meeting the same fate barely six months later in 1870, times must have been very turbulent for the company. Sun Fire Office records show the High Holborn works had fire insurance in 1823, 1824 and 1825 – insurance was in place in 1869 to cover the High Holborn fire but the fire at the new factory at Nine Elms wasn’t insured for some strange reason.

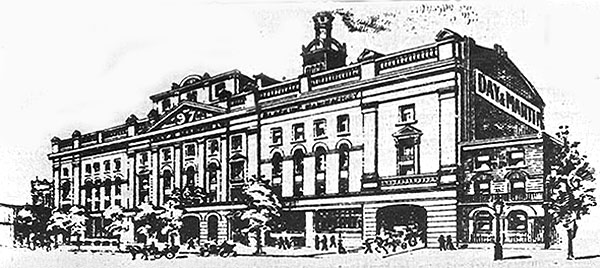

Day and Martin's new Borough Road works

In 1887 the signed a contract to buy a site on Borough Road, SE1, from R & J Pullman. Pullmans remained in possession of the property for two years and agreed to let a hoarding to a firm of advertising agents to generate some income. When Day & Martin were building on the site in 1889 there was a legal dispute as to who was entitled to the revenue, Pullmans or Day & martin. The dispute led to Pullmans making a charge of libel. The charge wasn’t upheld and the case became an illustration of the Law of Tort.

In 1887 the signed a contract to buy a site on Borough Road, SE1, from R & J Pullman. Pullmans remained in possession of the property for two years and agreed to let a hoarding to a firm of advertising agents to generate some income. When Day & Martin were building on the site in 1889 there was a legal dispute as to who was entitled to the revenue, Pullmans or Day & martin. The dispute led to Pullmans making a charge of libel. The charge wasn’t upheld and the case became an illustration of the Law of Tort.

They moved into their splendid new-built premises at 47-60 Borough Road in 1889. The most spectacular feature it that the façade is a fairly faithful reproduction of the High Hoborn premises, in scale and in detail. While certainly grand, its features were rather more restrained than the more monumental style of High Holborn, with stylised columns rather than the full Doric columns of old. Built of yellow brick with stucco dressings the factory was hidden behind the offices was covered with a curved corrugated-iron roof. It had four storeys, basement and full attic to centre. Projecting centre 5-bay and end 1-bay sections, articulated above ground floor by flat, giant pilasters with decorative capitals supporting entablature with frieze and cornice; balustraded parapet over, except for central 3-bay section which projects farther, with pediment over 4 fluted, giant, modified Ionic columns. Above this section is attic storey with pilasters and central segmental pediment with acroteria. Banded rusticated stucco to ground-floor with cornice. Openings in main features round- or segmental-arched with voussoirs, except those of central feature outer bays, which have shouldered, battered architraves and pediments. Wide, flat-headed windows in intermediate sections have pilasters and entablature. Plain 1st-floor windows under recessed stucco panels. 2nd-floor windows are round-headed with stucco archivolts (except for those in end sections and outer bays of central section, which are square-headed with architraves, console bracketed cornices and pediments). Gauged, flat brick arches to 3rd-floor windows with bracketed stucco sills. All 1st-, 2nd- and 3rd-floor windows are sashes with glazing bars.

They moved into their splendid new-built premises at 47-60 Borough Road in 1889. The most spectacular feature it that the façade is a fairly faithful reproduction of the High Hoborn premises, in scale and in detail. While certainly grand, its features were rather more restrained than the more monumental style of High Holborn, with stylised columns rather than the full Doric columns of old. Built of yellow brick with stucco dressings the factory was hidden behind the offices was covered with a curved corrugated-iron roof. It had four storeys, basement and full attic to centre. Projecting centre 5-bay and end 1-bay sections, articulated above ground floor by flat, giant pilasters with decorative capitals supporting entablature with frieze and cornice; balustraded parapet over, except for central 3-bay section which projects farther, with pediment over 4 fluted, giant, modified Ionic columns. Above this section is attic storey with pilasters and central segmental pediment with acroteria. Banded rusticated stucco to ground-floor with cornice. Openings in main features round- or segmental-arched with voussoirs, except those of central feature outer bays, which have shouldered, battered architraves and pediments. Wide, flat-headed windows in intermediate sections have pilasters and entablature. Plain 1st-floor windows under recessed stucco panels. 2nd-floor windows are round-headed with stucco archivolts (except for those in end sections and outer bays of central section, which are square-headed with architraves, console bracketed cornices and pediments). Gauged, flat brick arches to 3rd-floor windows with bracketed stucco sills. All 1st-, 2nd- and 3rd-floor windows are sashes with glazing bars.

The Borough Road site was in use at least until 1925.

In 1919 Day & Martin Limited (limited status was in 1896) were bought by Hargreaves Brothers and Co of Gipsyville, Hull. Hargreaves were makers of black lead and metal polish established in 1868 who had had an acquisition period of some 20 years, taking over W. G. Nixey (black lead manufacturers), Aladdin Polish Co (metal polish manufacturers) and others. In 1922 Reckitt & Sons acquired Hargreaves Brothers due to the losses the company was making. Hargreaves controlled about 20 companies in London, Bristol, Manchester, Liverpool, Birkenhead, Edinburgh and Montreal. Mr Hargreaves undertook not to enter any similar trade for 20 years.

By the early 1920’s they had established world-wide overseas trade and the Day & Martin product range now included floor polish, harness composition, metal polish and various shoe and leather dressings. In 1923 the directors sold the Day & Martin Ltd company to Carr & Sons, the highest bidder. Blacking manufacturers Carr & Son who were an equally famous firm established in 1837. The new firm of Carr & Day & Martin Limited still sold their boot polish products under the trade name of “Day & Martin’s” for many years. Carr’s factory was at Brunswick Park Road, New Southgate, London N11 and at some time, probably not long after the acquisition, the Day & Martin Borough Road premises were vacated and production moved to the New Southgate factory.

The premises were shared with John Dale Ltd (originally founded by John Dale Carr in 1890 as the John Dale Manufacturing Company, then in 1934 John Dale Manufacturing company Limited, later John Dale Limited) who made metal tins for both Day & Martin and Carr & Son (as well as a wide range of other metal products) and their need for larger premises was one of the reasons for C&D&M to move polish production to Great Dunmow, possibly as early as 1936 where they remained until a move to Wilmslow, Cheshire, in 1989.

The premises were shared with John Dale Ltd (originally founded by John Dale Carr in 1890 as the John Dale Manufacturing Company, then in 1934 John Dale Manufacturing company Limited, later John Dale Limited) who made metal tins for both Day & Martin and Carr & Son (as well as a wide range of other metal products) and their need for larger premises was one of the reasons for C&D&M to move polish production to Great Dunmow, possibly as early as 1936 where they remained until a move to Wilmslow, Cheshire, in 1989.

By 1949 John Dale Ltd had five factories with production, servicing, building, engineering and research departments and were making non-ferrous tubes and extrusions, tin-plate stampings and containers, plastic mouldings, aluminium ingots and castings. A separate company ‘New Era Domestic Products Ltd’ sold the aluminium domestic kitchenware ‘Daleware Holloware‘ that was made by JDL. John Dale Ltd were certainly still at New Southgate in the 1970’s where they made plastic as well as metal packaging and also had premises at Waterfall Road, New Southgate. John Dale Ltd were bought by Metal Closures Group in the 1970’s but the area of the works is now demolished and is now a large industrial estate.

In 2006 the Day, Son & Hewitt Ltd and Carr & Day & Martin Ltd companies were acquired by Tangerine Holdings Ltd, a family business formed in 1994 and based in Lytham, Lancashire, which has a portfolio of companies that manufacture and market nutritional health products for farm & companion animals.

Carr & Day & Martin Ltd at their Alderley Road, Wilmslow factory, under contract to the MoD, made an army portable stove called the Pypro Cari-Cook. This small device forms a stand on which a mess tin or mug can be stood and heated with a block of hexamine.

Carr & Day & Martin Ltd at their Alderley Road, Wilmslow factory, under contract to the MoD, made an army portable stove called the Pypro Cari-Cook. This small device forms a stand on which a mess tin or mug can be stood and heated with a block of hexamine.